Praise is easily given but the proof is in the fruit. If in the following pages I seem effusive in my praise of Ted Weaver it is because I have known this man and I know that he deserves it.

I am the youngest son of Ted and Sylvia Weaver. The story you are about to read is my father's story but in many ways it has become my story as well. Some of my earliest, most indelible memories include campfires, family gatherings and my dad telling his war stories. This was the beginning of my interest in World War II, born late at night as I drifted off to sleep while Ted's sonorous voice, sometimes excited, sometimes sad and serious, told tales of a midair collision on D-Day, a direct hit from 88mm anti aircraft artillery and people dying for reasons I could not yet comprehend.

As I grew older my interest in WWII grew as well, primarily through my hobby of building model airplanes and tanks, especially tanks. As my skill increased, my research into uniforms and insignia sparked a desire to learn more about the men who fought and died in those war machines. I read histories and biographies and through my reading I learned something of what it cost in terms of human suffering and sacrifice to secure the freedoms that we too often take for granted. I also learned something of what Santayana meant when he said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." But what is it that we are to remember from the past and what are we to avoid repeating?

For the longest time I have wanted to tell my father's story but I never quite felt equal to the task. It wasn't until I was preparing a presentation of Ted's experience hiding with the Dutch underground that I remembered an admonition I had received more than three decades ago. The recollection came so forcefully and in such a rush of detail and emotion that I was thunderstruck; how could I have forgotten this event?

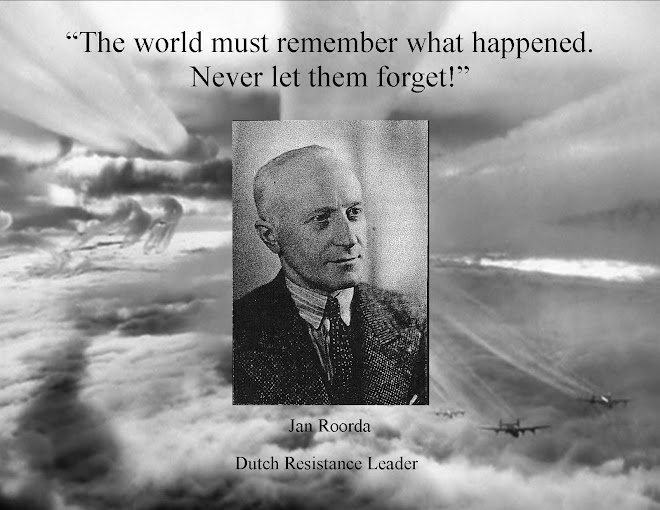

It was 1974, Jan and Rien Roorda were visiting my father and family here in the

Dad brought Jan to my room to see my model collection. Jan showed genuine interest and I was pleased to show off how I had painted the tiny, little insignia on the soldiers' uniforms in detail. Then Jan picked up a model of a German Sturmscharfuhrer of the SS with his swastika armband. Jan examined it for a long moment and I began to worry that he might be offended at the sight of it, but he wasn't. In fact, he pulled out his wallet, gave me some money and encouraged me to continue my hobby. Then Jan looked me in the eyes and in a gentle but firm voice, he said this, "The world must remember what happened. Never let them forget!"

As I look back over the past thirty-six years since Jan uttered his admonition I see why it is so important for me to fulfill his charge. The world has largely forgotten, and worse. We still commemorate those who served; we study the battles and visit the battle fields but do we remember why we fought? World War II provided a backdrop against which certain principles and values were brought into sharp contrast. There are socio-political philosophies of life and living that are conducive to a peaceful, happy existence. And there are other philosophies that have inflicted immeasurable suffering upon untold millions during the war and for decades after. These opposing principles hinge upon the use or misuse of agency, the protection or the suppression of individual freedom and the irrevocable link of that freedom to responsibility and accountability.

We are fast approaching a crossroads in the history of this world where we risk suffering the same catastrophic social upheavals our parents and grandparents had to endure. It shouldn't take a world at war to convince us that agency, accountability and compassion are indispensable to civilization. We shouldn’t have to loose our freedom to learn that these principles can only flourish in a society governed by the rule of law, not by the rule of any one political entity or personality.

Compassion originates in the heart of the individual, not from an edict of the state. But it can be modeled; it can be emulated. If we surrender our individual responsibilities to the state in exchange for the mirage of social equity forcibly imposed, if we allow the complacency of self indulgent gratification and an attitude of entitlement to become the accepted, fundamental nature of our humanity, we will reap the natural consequences of conflict on a grand and terrible scale. I say natural because, conflict is the outward manifestation of the inward character. Again, compassion originates in the heart of the individual. Crises peal away the facade of civility and reveal either a healthy character that will stretch and grow because of the opposition or a cancerous character that will kill its host in a blind, frenzied attempt to perpetuate its own survival. The fall of every great civilization began with the soul decaying march into egocentrism. Or as Arnold Toynbee put it, “Civilizations die from suicide, not murder.” The kind of character that halts this suicidal trek cannot be bought with any amount of government funding. And as Richard G. Scott has said, “Character is not forged in the heat of battle when we are challenged. It comes quietly from decision after decision made with the proper use of agency. It is used when challenge is upon you.” We may or may not be born with compassion but to whatever degree we posses it, compassion must be nurtured and developed if we (and the society in which we live) are to survive and flourish.

It is my sincere desire that through telling Ted's story I might keep alive the memory of those who, like my father, lived lives governed by accountability, guided by compassion and who freely exercised their agency for the benefit of others. Ordinary people like you and me who stood at a dangerous crossroads and had the courage to allow their compassion to override their fear. I have come to realize that Ted's story is really only one thread in a tapestry of lives that have been woven together to bear witness, a tapestry of light shining out from one of the darkest epochs of modern history to testify to the worth of the individual, the sanctity of life, and the ability of one person to make a difference. Ted's rescuers demonstrated how seemingly insignificant acts in the face of apparently insurmountable opposition can literally change the world. They certainly changed mine. They risked their lives and gave their lives for the cause of freedom and human dignity. They recognized our mutual humanity and freely chose to be a force for good instead of just a force for self. It is my hope that their courageous examples might inspire more of us to become rescuers in large and small ways. Perhaps we begin by asking ourselves if we have ever needed the compassion of a total stranger and then respond by being willing to offer a stranger an unexpected kindness.

Excerpt 2 From Chapter One

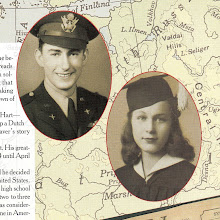

Mary Daines Weaver stood all of five foot two inches tall and weighed ninety pounds soaking wet; her husband Mark measured in at five foot seven. When their first son Ted Lionel Weaver was born December 16, 1921 weighing in at ten and a half pounds, measuring twenty-one inches, they suspected that he would grow up to the stature of a sizable man, and he did. What they did not know - although I suspect Mary knew - was the stature of character Ted Weaver would attain to. Ted did in fact grow taller than his father, six foot and then some. After Ted, came two brothers, Van and Don and then their sister Betty. They were well suited to the frontier life of their early childhood in

Mark Lionel Weaver was a man of many talents. He grew up in a musically inclined family, playing the violin for the dance band his brothers and sister organized to help pay their way through college. Mary was an accomplished dancer and choreographer and Ted spent a fair amount of time as an infant in a bassinet set on top of the piano during rehearsals. Ted often attributed his love of music to that early exposure. When he was still too small to play the guitar his father tuned a violin like a guitar so Ted could play it. Ted’s love of music continued to grow and his talent for playing just about any instrument he picked up continued to expand.

Ted attended second grade in

"It became my job to herd a couple hundred head of wild horses outside the pasture day times so the grass would hold up for the night inside the pasture. Several times a month they would make a break for it and head for the farms outside of the forest. Wild chases always ensued followed by long, dusty rides back to the ranch. On one such race to beat the herd down to the road at the end of the meadow, I decided to try a Tom Mix bounce from one side of the horse "Paint" to the other. He was running full out in front of the herd and I made two swings from left to right, then back to left. I must have pulled him off balance or he stepped in a gopher hole or something because he stumbled and fell with me. I could see the herd closing in on me and for the first time that day, I got serious. I managed to catch Paint and get aboard again in time to avoid being trampled to death. I still managed to get in front of the herd and get them turned back to the upper end of the meadow. Luckily no one saw the escapade, so I didn't get a 'Scotch blessing' because I never squealed on myself."

The family lived in

One summer during his early teen years Ted had a job wrangling horses for a surveying team in the

Excerpt 3

The B-24 had the best range of all the heavy bombers in

As Ted began to climb out of his seat he looked out the cockpit window and saw his commanding officer tearing out to the parking pad in his jeep looking none too pleased. Once out of the plane, Ted called the crew to attention and saluted the C.O. “What in blazes were you doing landing with one of your crew members sitting on the bomb bay cat walk?”

Ted turns to the crew and asks, “What is he talking about?” At this point Joe steps forward and says, “Well, Skipper I didn’t want to worry you when you were coming in to land but when you made that dip to signal breaking formation over the field, we had a bomb go out and it took the door off the track. I had to go out on to the cat walk and hold the door up so it wouldn’t hit the runway when we landed.” Unlike the B-17, the belly of the B-24 hung low to the ground because the wings were high on the body. The bomb bay doors were designed to open by rolling upward – instead of swinging downward - much like a garage door does, to facilitate the loading of bombs while on the ground. If they were forced off their tracks they would hang down low enough to hit the ground upon landing. Joe had sat on what amounts to the keel of the plane - a walkway less than a foot wide - that runs the length of the bomb bay between the tail section of the plane and the flight deck in the nose. On this precarious perch he had somehow managed to hold the broken roll up door high enough to prevent it from hitting the ground when they landed.

It took three days to find out what had happened to the two bombs that dropped out of the ship near the landing field. Finally the Yankees at Shipdham received a call from an irate English woman. She couldn’t hang out her laundry to dry because there were two bombs in her back yard between the house and the clothes line. She had been away from home when they fell but it was never-the-less a great blessing that neither one had exploded upon impact.

By the time Ted and his crew had flown twenty missions, a tour of duty had been raised from twenty-five to thirty-five combat flights. This was largely because the German fighter aircraft were no longer able to follow our bombers back to

During the course of Ted’s tour of duty he had taken all of the events of his combat missions rather matter-of-factly. It is a common thing for veterans to refer to the ordeals they survived as just part of the job, “I was just doing my job,” they say. Ted often used that same phrase, “We had a job to do…” But on the eve of Ted’s twenty-third mission something was different, he was puzzled by a strange feeling, a feeling that he was in a totally unfamiliar place. The only thing unusual about the next day was the fact that Ted's ship would have a replacement crew member along. While Charley Harrison was recovering from his head wound, his replacement would be Sgt. Stanley Nalipa.

Ted remembered that evening and his feeling of disorientation vividly. It was one of the details of his story that he never omitted when ever he recounted it. Of this feeling of displacement he said, "At first I thought it was just that I had been moved recently to new quarters in a room by myself. Until then I had bunked along with about nineteen other officers in a large Nisson hut. I thought, I had better write to Sylvia. Then I said to myself, oh I'll wait until tomorrow when I'm not so tired, the mission I flew today tired me quite a bit. Something warned me not to wait, but to write Sylvia a short note anyway. So I sat down and wrote to Sylvia before I went to bed. When I finished the letter, I still felt like sort of a premonition of something foreboding. I knew that I was scheduled for a mission the next day, but I had never worried about that before. I really wasn't worried; it was just kind of a funny feeling. It seemed the sarge came in to wake me before my eyes had hardly closed, 'Weaver, breakfast in a half hour, briefing at 01:00 hours.'"

The mission was to bomb an aircraft factory in

First off, Ted's parachute was missing, loaned out to a new pilot and no time to properly adjust the replacement chute. The excuse was given that the chute packers hadn't expected Ted to be flying mission that day. There was nothing to be done except hastily fit another chute and head out to the flight line. That was just the beginning. The plane they were assigned was 42-99966 W - Full House - not one of Ted's favorite ships. He had gone up in Full House the day before for bombing practice and he didn't like the way she handled. He also didn't like the fact that she had taken a direct hit by 20mm flak to the starboard main wing spar, especially given what he had seen happen to the bomber with the run away engine. When he got to the ship, more good news: jammed gun turrets in the nosse and the tail, a gummed up waist gun. One of Bart's duties as co-pilot was to pre-trip the plane and check for any problems including starting up the engines. He hadn't done it. When the engines were started up there was a strange noise from one of them. Ted instructed the crew to keep working on the gun turrets and went to see about taking the spare ship up; another crew had already claimed it.

Things were off to a bad start but it would take a lot more than that to stop this crew. Ted had the option to abort if, in his opinion, the ship was not found to be airworthy or combat ready. He also knew that senior officers could develop a bad attitude towards a ship's captain who aborted a mission without having a good reason so Ted decided to use the time they had to continue working on the faulty equipment. By the time the red flag went up, the nose turret was working and the waist gun was back in action. They figured they could work on the tail turret during the flight over the channel. All of them were anxious to get one more mission under their belts, one more mission closer to finishing their tours of duty, one more mission closer to home. After all, this was

As they approached the target over

Ted had Don, the radio operator, try to contact the squadron commander to inform him that it was obvious that they would not make it back to England and had his co-pilot Bart try to contact their lead plane to tell him that they were dropping out of the formation. One by one the radios proved to be inoperative until Bart was able to make contact with a P-51 fighter escort on "C" channel. He said he would relay the message to the group leader. Then Bart made contact with a couple of P-38s who flew cover for Full House and another bomber from the 68th squadron, the Patsy Ann II that had also been hit in the first wave. Crippled bombers were especially vulnerable to German fighters and the P-38s helped successfully repel another attack by Messerschmitt Bf-109s. The intercom was knocked out so Ted had to shout back to the radio operator to go check on the crew's status.

Well I won't burden you with all the gory details but suffice it to say that things were getting pretty hectic in the cockpit of Full House. With hydraulic fluid all over the rudder pedals making controlling the plane more than just a little challenging it was not a happy discovery that the controls to feather the starboard engines had been blown away. It took all the strength of both Ted and Bart to hold Full House from rolling over on her right side and dropping out of the sky. And to add insult to injury, the two dead engines on the starboard side were pulling them in to a right hand turn, deeper into Most people with a casual knowledge of WWII history know of the infamous Bataan Death March. That grueling, bloody trek down the Bataan Peninsula that left 80,000 men dead from road side executions, beheadings and exhaustion. It was certainly not the first atrocity committed during WWII but it is one of the more infamous ones. Less well known is the 500 mile, three month march that Allied POWs were forced to undertake during Europe’s bitterest winter in modern history. Joe Gnaidek and Lorin Voight survived that crucible of starvation, cold and brutal murder. I feel ashamed that I cannot speak with more certainty about whether others on Ted’s crew endured that march. It does not sit well with my conscience that I am so ignorant of my own father’s crew and what they suffered. It does not sit well with my sense of responsibility to be a voice of remembrance that the beneficiaries of the freedom purchased with that suffering have either squandered it, defaced it or cast it away in pursuit of a lie. Never did the maxim, “Cheaply gained, lightly esteemed,” ring more true for me than it does today. The irreverent, disrespectful attitude that is so pervasive in our culture makes me hesitate to share the following story because of the sacred nature of it and yet, it is of utmost importance to my purpose of being a voice of remembrance that I share it. And it is with great reluctance that my mother granted me permission to do so.

While Ted and his comrades were engaged in their life and death struggle above

Now you may believe that this is just some kind of freaky coincidence. And you may believe that there is no God and that you can do whatever you want and never have to account for your behavior or suffer the consequences thereof, but the fact remains that, “There’s a Divinity that shapes our ends, rough-hew them how we will.” When we begin to recognize and acknowledge that Divinity, we begin to mature in ways that can never happen if we insist on rooting ourselves in the self indulgent, navel-gazing egocentrism that plagues the nations. We also begin to recognize that the law of the harvest applies to our lives as well as to our crops. The courage to be a Jan and Rien Roorda or a Berend Shoemaker does not randomly spring up from the soil of selfishness, nor is it a spontaneous event prompted by the particular alignment of certain planets. Courage grows in the soil of character nourished by charity; charity meaning the pure love of God for our fellow man. That kind of character is not, as Richard G. Scott has said,”…forged in the heat of battle when you are challenged. It comes quietly from decision after decision made with the proper use of agency. It is used when challenge is upon you.” The gift and ability to see and feel and know what the eye can’t “see” comes the same way. So God gave Sylvia a tender mercy and she recognized it as such. He did not remove the burden but he did make it lighter to bear, as promised. “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” Matthew 11: 28-30. My parents lived by those words and I have not only witnessed the fruit of them time and time again, but have also been the beneficiary of them as well.